On Friday, Oct. 8, 2021, a new California law requiring high school students to take an ethnic studies course was passed under Assembly Bill 101. Though the law will apply to the class of 2030, FUHSD schools will begin requiring the class for the class of 2029.

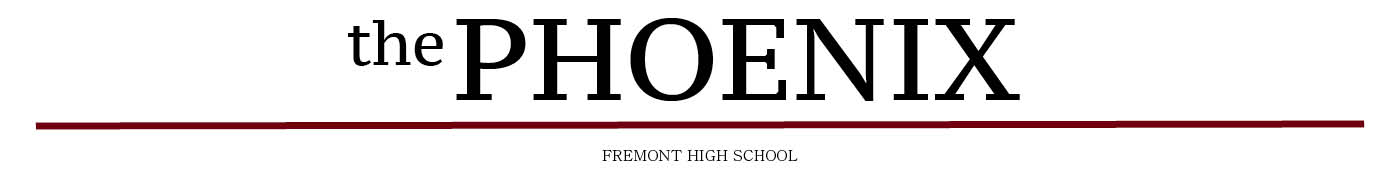

“[Ethnic studies] tries to present information in a way that is unbiased and allows for students [to] explore from their own experiences and to be able to access the curriculum,” FUHSD Superintendent Graham Clark said. “[They’re] able to make sense of the information and how that might impact them and the world around them.”

In the 2023-24 school year, FUHSD ran a pilot program for the course at Monta Vista High School and FHS. Although the specifics of course curricula vary, FHS ethnic studies teacher Viviana Torres explained that students learn about four overarching topics: identity, community, systems of power and activism.

Overall, Torres believes the differences between ethnic studies and other school subjects is what makes the class meaningful. She hopes that the course continues to impact students long after they have taken it.

“I think [the course is] going to make students better learners by thinking about power and agency,” Torres said. “[Questions] like, ‘What is my role in where I am right now?’ and ‘How can I think a little bit differently about what I want in this space?’ rather than just coming in, being a passive body that’s moving from class to class.”

FHS planned to offer another pilot of the course this year to get more feedback on the program, but ultimately decided against it.

“We want to make sure that we offer the sections [that] students sign up for,” FHS Principal Bryan Emmert said. “We didn’t have enough students sign up for [ethnic studies], so we’re not offering it this year.”

The decision to make ethnic studies a high school graduation requirement is unprecedented, sparking discussion about its impact on FHS students. Robert Javier, FHS English teacher and former Equity Chair, noted that the execution of the pilot course was very different from what was planned by the teachers and administrators who, as part of a collaborative, discussed the best approach for the course.

“Knowing [the] whole reason why ethnic studies was created and fought for as it was almost 50 years ago, [the learning collaborative] felt it was going to be beneficial for students at the 11th and 12th grade level, [as a] year-long [class],” Javier said. “Whether that was in tandem with US history, or if it was paired with econ/gov, or [as] an additional course altogether.”

Javier added that, as a part of the collaborative, he and other teachers had looked at several sample curricula from other schools as resources during their discussion. Ultimately, the district’s approach to implementing ethnic studies differed from the recommendation in several respects. The class was offered as a half-semester at the ninth-grade level, paired with a health class.

“[I’m] concerned [as] to what extent ninth grade[ers] really comprehend [ethnic studies] without the context of American history,” Javier said.

Despite their reservations, teachers agree that the course enables high schoolers to have critical discussions, and is an important course offering regardless of potential curriculum disputes.

“[Ethnic studies] allowed students to decide for themselves who they are,” Torres said. “Even though everybody had the same vocabulary around like race, gender and social identity, we gave students the ability to talk about and describe themselves in ways that felt true to them.”