The isolation of the COVID-19 lockdown fundamentally changed millions of people’s relationship to food. As the prospect that quarantine was a long-term policy in our lives set in, two trends emerged in the manner we got our food. Home cooking and food delivery services using companies like Grubhub, DoorDash or UberEats may seem inherently contradictory at first sight. Home cooking requires personal involvement in one’s food whereas food delivery isolates customers from those making it and delivering it. However, both have their spikes in popularity rooted in the culture and environment of the pandemic.

Food delivery, as useful as it may be in the modern day, reached its dominance during the pandemic. According to the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, customer spending had increased by 70% in 2021 compared to 2019. The perceived need for such a service was obvious. With as little human contact as possible, a person could reduce the risk factor in obtaining their food by sending a gig worker out to do it for them. The extra charge was worth it to many upper-class consumers to isolate themselves as much as possible from the outside world. One would assume that once the lockdown was lifted, the growth of these delivery services would decrease. Yet with record profits still being reached each quarter, it seems that more and more people rely on the convenience and novelty of these services rather than in their practices of isolation.

Still, the isolation is retained as a feature, intentional or not. As one scrolls through a faceless app with high-quality pictures of food, it replaces interaction with the cashier at the register. One does not get the moment of someone handing off their order, for most workers automatically do “no-contact” delivery with only a picture of the food in front of their door confirming their order has arrived. From every step of the way, these services abstract each level of human interaction to button presses, taps and swipes.

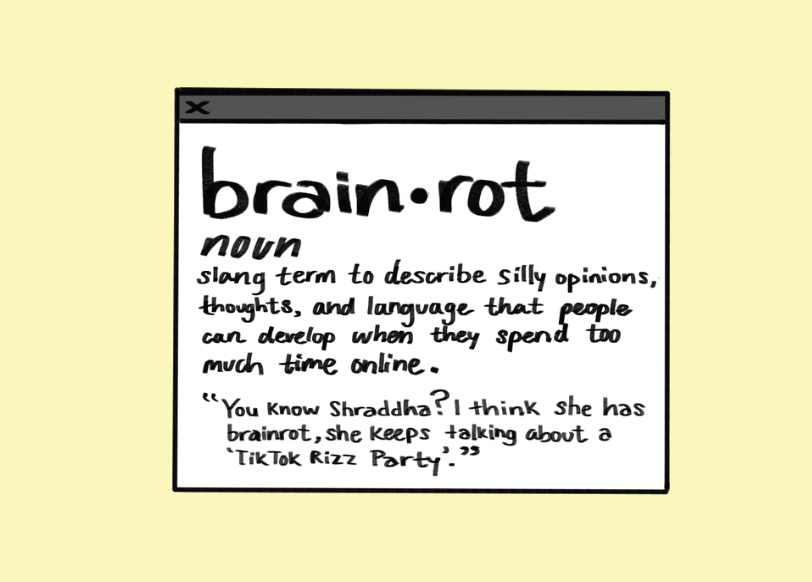

But with the rise of home cooking, one would assume that it was a natural counterpart to food delivery services. According to a Statista survey, almost 60% of people have stated that they cooked more often at home than before the lockdown. More people could cook and spend time with their families. However, social media’s effect in influencing what is cooked is significant. With Instagram and TikTok’s ability to show short-form content with highly edited, “aesthetic” versions of food, the average person with a suddenly inordinate amount of time could finally make and eat these foods.

Furthermore, the things that power these food trends remain consistent throughout the years. For many creators, they must make content for a living. The idea of eye-catching foods, meant to generate revenue for their creators through these social media sites, has ultimately affected the home cooking side of social media.

One of the most subtle forms of this maximization culture is the replication of “restaurant” food. There are hundreds of videos attempting to replicate “restaurant quality” foods. No longer is it about cooking food that satisfies one’s family or oneself but rather the creation of food that has a mystique and some attempt at professionalism imbued into the attempts to make restaurant-style foods. They are attempting to replicate the attachment to the brands when it is not well suited to the economy of scale and the coordination of labor of home cooking. The maximizing culture of the home cooking scene abstracts the food we eat into brands, ideas and content rather than the actual taste or experiences we share with other people.

These two seemingly divergent cultures similarly abstract fundamental parts of food. Food delivery abstracts the labor behind your food, while home cooking abstracts the food itself.