Women’s History Month: The coolest women on the coasts

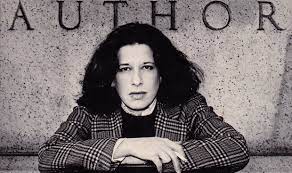

Photo courtesy of Rookiemag

I’ve been mad about Joan Didion – even before I read her writing – since I saw the photo of her smoking against a Corvette. It’s strange that a photo of a writer had as much impact as their writing, but the shot of Didion leaning back in a floor-length dress, smoke clouding her face, revealed a personification of complete control and self-assurance. I wanted that kind of coolness, the detachment that involved absolute trust in oneself and a disregard for the opinions of others.

When I was young a lot of the people I wanted to be were men. Men who walked unhindered by insecurities and lapses of judgment: Wolf-of-Wall-Street-type guys, tech guys who acted like jerks but got away with it because they were geniuses. I saw this ability to elude conventional norms as a sign of a supreme self-confidence that would be inevitably followed by success. The world turned a blind, dare I say congratulatory, eye because the men were so self-assured that we were assured as well.

Didion represented a flip-side, a feminine side, to that self-assurance. Her’s took the form of a certainty and trust in expression, a distinctive and exclusive style. And that certainty and style – that to me defined what it meant to be a women writer.

“Let Me Tell You What I Mean”, Didion’s new book, is less stylish than her other essay collections (The White Album, Slouching Towards Bethlehem) as it’s less of a carefully curated collection than it is a collection of yet-unused essays, but it is still her voice, her certainty. One essay “Getting Serenity” documents a sitting-in with a Gamblers Anonymous. It reads very similar to fiction because of its first-person perspective, Didion describes the various confessions and her reaction, but what is surprising is that it ends that way – like fiction. Frank L., one of the gamblers at the meetings, is being celebrated for a year of sobriety. “It hasn’t been easy,” he says. “But in the last three, four weeks, we’ve gotten a…a serenity at home.” At this, Didion writes: “I got out fast then, before anyone could say “serenity” again, for it is a word I associate with death, and for several days after that meeting I wanted only to be in places where the lights were bright and no one counted days.” This testimony is significant because it becomes the entire point of the essay, her emotional response. The traditional essay breaks from trying to convince you to just telling you what it is. That trust in her instinctive reaction, that her writing is simply a search for her instinctive reaction, is striking. It represents a voice that relies on itself, a gaze that turns inwards.

—

While I was reading “Let Me Tell You What I Mean”, I was also watching Pretend It’s A City, the Martin Scorsese docuseries centered around Fran Lebowitz. Didion is famously a Los Angeles writer, but Lebowitz is aggressively a New Yorker, and the series follows her around New York as she expels her opinions about everything.

In keeping up with the idea of certainty and style, Lebowitz undeniably has both. A chain-smoking, perpetually complaining writer/humorist (public figure?), she wrote a column for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine and was a regular guest of David Letterman. She has a uniform of cowboy boots, Levi’s 501 jeans, a Savile Row blazer and a frown, and she’s indisputably one of the coolest grouches in New York.

Whether or not Lebowitz is still actually a writer isn’t clear – apparently, she’s been suffering from decades-long writer’s block. For the past forty-years-or-so, she’s been making a living doing public-speaking, talking about politics, race, gender, art, culture and of course, New York. Pretend It’s A City compiles a few clips of Lebowitz’s speaking events, but the majority takes place either at a circular table with Scorsese or at interviews with celebrities like Spike Lee or Toni Morrison. While she speaks, Lebowitz name-drops frequently with the nonchalant air of someone who’s used to being around the famous. Between stories of dinner with Duke Ellington and sitting front row at the famous Muhammad Ali v Joe Frazier fight, you get the sense that when she was young, she really lived. “Because of sex, that was the whole point of going out,” she says in an interview with the Paris Review. She goes on to say that the nightclubs “were covert….Now they read about it in the suburbs, and it’s just like going to the movies. It’s the same people – the general public. And I’m not a general-public fan.”

“I’m not a general-public fan”: a perfect encapsulation of Fran Lebowitz. And also why Pretend It’s A City is so charming and funny. Her opinions are compelling yet soothing, even when the delivery appears so contrarian. Don’t we all love nice things and hate normal people? You get the deluded sense that Fran and you would get along; none of us want to consider ourselves part of the general public.

—

Earlier I said that certainty and style defined the woman writer, but now I hesitate to stand by that sentence because within it is a hint of artifice. For what is certainty and style if not something self-cultured? Lebowitz and Didion are both the type of sixties/seventies woman writer that people identify – along with Susan Sontag, Patti Smith and Eve Babitz among others – as style symbols. Style icons who are an embodiment of a certain type of taste, both theirs and yours. But like a coffee-table book, they display a curated idea of living that is ultimately unattainable.

Is that the female writer? An icon in the star-like sense? Someone with an affected self-assurance, someone who lives style but also can create it. Didion with her focused intelligence and casual coolness, Lebowitz with her wit and supercilious nature.

I think of how many times I’ve reverently read Didion’s packing list in “The White Album” and I can’t help but notice that the best writers become lost as their own characters. Carefully crafted, they forever wander in their own worlds, stuck in the mood of a Los Angeles in a state of dissolution or a New York where people live fast and hard and opinionated.